There was some pretty big news in math last week. A mathematician has claimed to have proven the Riemann Hypothesis, and if he is correct, he will win $1,000,000.

Why is there such a big prize for a math problem? This problem is one of the Millennium Prize problems, which is a group of seven problems that are fundamental to a branch of math. The Riemann hypothesis, if proven, has vast implications in number theory and in prime numbers. The distribution of prime numbers is chaotic, and although we have found some patterns in the distribution, the Riemann hypothesis would give us much more insight into the distribution.

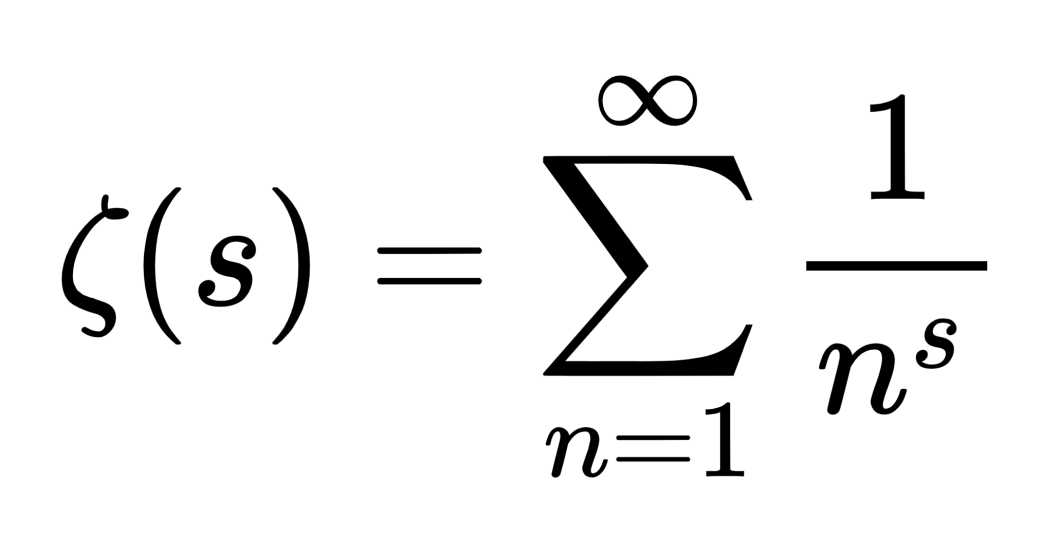

The Riemann hypothesis stems from the Riemann Zeta function, which is an infinite sum at every point.

One pattern mathematicians have found is the Ulam spiral. One can create the Ulam spiral by starting in the center at 1 and spiraling out. Every black dot is a prime number. The Ulam spiral has black diagonals, which give some semblance of order in the otherwise chaotic jumble of dots.

But this does not help us predict where a prime number is very easily. I can follow a diagonal of black and find the “expected” value of a prime number, but sometimes, there are holes in the diagonals, and the expected value of the prime will be slightly off. The Riemann hypothesis gives better predictions for the placement of prime numbers.

There is a function that gives the number of primes below a certain integer. The function’s validity hinges on the Riemann hypothesis being true. If the mathematician in the news has successfully proven the Riemann hypothesis, I could plug in a very large number into the function and get the number of primes below that number. I could then put the number that is four less than the original into the function, and if that output is less than the first output, then I know that one of the numbers I passed is prime. This test is much more efficient than the basic primality test: divide the number by every possible divisor.

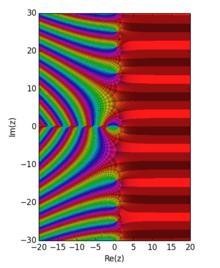

The Riemann hypothesis also helps us find prime numbers by allowing us to calculate the exact deviation of the prime number from its expected value. The calculation of the deviation involves the set of all zeros of the Riemann zeta function, so if the nontrivial zeros all have a real part of 1/2, the calculations would be relatively easy.

As I write this, other mathematicians are showing skepticism of the proof, but if the proof is valid, this will advance the field of math to a new level.